By SIMON ROMERO and JUAN FORERO

By SIMON ROMERO and JUAN FORERO

Published: May 3, 2006

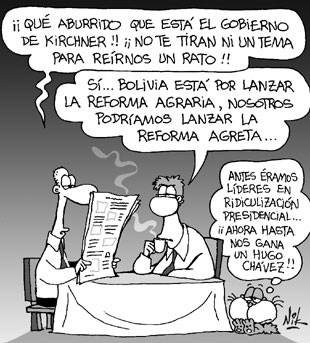

Bolivia's nationalization of its energy industry, announced Monday by President Evo Morales, was a vivid illustration that the populist policies, championed most prominently by Venezuela, were spreading.

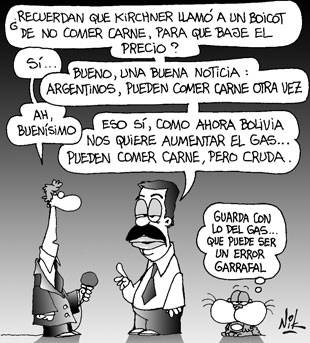

The impact on international energy markets is expected to be minimal because Bolivia produces mostly natural gas and exports it to just two countries, Brazil and Argentina.

Symbolically, however, the dispatch of troops to refineries and oilfields threatens to inject more nationalistic fervor into the policies of Bolivia and other energy exporters, in Latin America and abroad.

"We're experiencing the supremacy of emotional politics at this time," Gonzalo Chávez, an economist at the Catholic University of La Paz in Bolivia, said in a telephone interview. "The nationalization was received with great enthusiasm, but we'll have to wait and see how the economic impact of all this plays out."

Many countries have already taken steps to assert greater control over their natural resources, spurred by nationalist politics and lofty energy prices.

Major oil suppliers like Saudi Arabia and Iran nationalized their oil interests decades ago. Russia recently reorganized its domestic energy industries as well. But it is in the Andean region where momentum is quickly building for a greater government role. Venezuela, a top supplier of oil to the United States, is at the forefront of this trend, recently forcing foreign energy companies to accept state control of important ventures.

Venezuela, a top supplier of oil to the United States, is at the forefront of this trend, recently forcing foreign energy companies to accept state control of important ventures.

Ecuador imposed rules in April that increase the state's share of windfall oil profits, while in Peru, Ollanta Humala, a presidential candidate, has called for a more aggressive government role in natural gas and mining operations.

On Tuesday, Bolivia's vice president, Álvaro García, said major mining companies would also have to pay higher taxes. "There are not going to be company expropriations, of course," he told a local radio station, according to Reuters, "but we're going to assume a greater level of state control."

The government said it expected the nationalization of its energy sector, which includes the second-largest natural gas reserves in Latin America, behind Venezuela's, to raise its annual revenues by more than $300 million, to $780 million.

"I don't think the game is over," said Lawrence J. Goldstein, president of the PIRA Energy Group, which is based in New York and is supported by the petroleum industry. "It's going to move from the Americas to the Africans. This is a very dangerous precedent."

Bolivia's step highlighted the region's changing political landscape, pointing first to the weakening influence of the United States, and to the rising profile of Venezuela's president, Hugo Chávez, who has been empowered by soaring oil revenues.

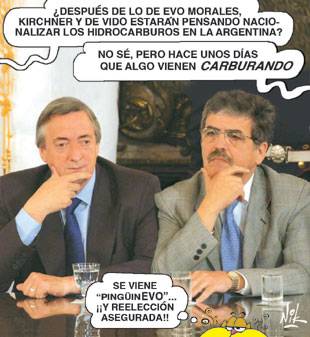

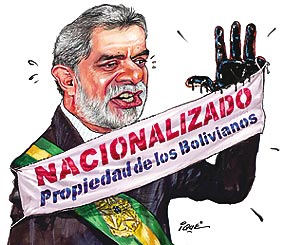

But it also threatened to open a schism among the region's new wave of left-leaning leaders. Brazil's president, Luis Ignácio da Silva, while nominally left-leaning, has drifted more toward the center since his election in 2002. Now he will have to negotiate a way out of the current crisis for his country, which is one of the biggest investors in Bolivia's energy industry and the main buyer of Bolivia's natural gas.

Brazil announced late Tuesday that Mr. da Silva would meet Thursday in Puerto Iguazú, Argentina, with Mr. Morales and with Argentina's president, Néstor Kirchner, to press for stability in energy supplies and prices. Mr. Chávez may also attend.

The Brazilian state oil company, Petrobras, the nation's largest company, is among the small number of foreign energy companies that will feel the brunt of Bolivia's decision.

At a news conference on Tuesday, André Singer, a Brazilian government spokesman, said Petrobras would maintain its Bolivian operations for the time being, though it remained wary of future investments.

Other energy companies affected include the BG Group in Britain, Repsol-YPF S.A. of Spain and Total of France. The only Bolivian investment of Exxon Mobil, the largest American oil company, is a minority stake in a nonproducing gas field controlled by Total.

The president of Repsol, Antonio Brufau, said the Bolivian decree fell "outside the norms and logic of business that should be the guides for relations between companies and governments."

Companies said they were waiting for more details to emerge and for negotiations or legal arbitration to begin with the Bolivian government, which has given them six months to agree to the new conditions or leave.

For the largest natural gas fields, the decree would give the government 82 percent control, including royalties, taxes and direct stakes, while that level would be lower for smaller fields.

But specifics remain to be clarified, in particular whether infrastructure or assets will be seized without compensation. The decree described earlier policies giving foreign companies a foothold as "treason."

Edward E. Miller, president of Gas TransBoliviano S.A., a company that operates part of the pipeline to Brazil, said people in the energy industry were still trying to make sense of the changes.

"We have military in front of our offices, but they're not doing anything but making sure people don't take anything out of the offices," Mr. Miller said in a telephone interview from Santa Cruz de la Sierra, in Bolivia. "They're not abrasive, they just don't want anyone to leave with laptops or documents."

In taking such a bold step, Mr. Morales appeared to have taken a cue from President Chávez, who has used his oil money to buttress alliances. In Bolivia's case, Venezuela has agreed to supply about 200,000 barrels a month of subsidized diesel, donated about $30 million for social programs and sent literacy volunteers into the Bolivian countryside.

Just a day before his nationalization speech, Mr. Morales entered into a trade agreement with Venezuela and Cuba called the Bolivarian Alternative for the Americas.

"Chávez is forcing Bolivia into a radical shift," said Roger Tissot, director of markets and countries for PFC Energy, a consulting firm in Washington. "That is the major headache for the U.S."

The Bush administration has quietly tried to engage the new Bolivian government, though that overture and Brazil's efforts to moderate Mr. Morales appear to have had little effect.

A perception that foreign oil and mining concerns have exploited landlocked Bolivia has been a driving force in the country's politics for decades. But it gained new currency after Bolivia and other nations in the region reopened the energy industry in the 1990's.

Since then, there have been boisterous protests and a tide of electoral revolts by voters who felt that the economic benefits had not spread to the poor.

Bolivians have also chafed somewhat at their dependence on Brazil. Petrobras controls 45 percent of Bolivia's natural gas fields, and part of a pipeline that supplies 51 percent of Brazil's need for natural gas.

At the same time, Brazilian companies, eager to expand into neighboring countries, have been struggling to do so without offending their hosts.

"Brazilian companies still do not have a nuanced approach, a diplomatic culture, particularly in relation to smaller countries," Luís Nassif, one of Brazil's leading economic commentators, recently wrote in the newspaper Folha de S. Paulo. "They are arrogant, like the British before World War II."

Yet while Brazil might feel tremors from Bolivia's decision, it is Bolivia that may be risking its potential as a major natural gas exporter.

Companies had been holding off on investments in Bolivia for some time, unnerved by growing talk of precisely the kind of step that Mr. Morales took this week. Foreign direct investment, much of which goes to energy and mining, fell to $103 million in 2005, from $1 billion in 1999.

What is more, unlike oil, natural gas is not easily exportable, with costly liquefaction facilities, customized tankers or pipelines needed to take the fuel to markets. Chile, a potential market for Bolivian gas, may choose instead a project to import the fuel from as far away as Africa.

Even Brazil, while now reliant on Bolivian gas, has recently discovered large offshore gas reserves of its own. Thus the window of opportunity for Bolivia to become a leading gas exporter may be closing, even as it grows more courageous in its dealings with foreigners.

"If Brazil decides to give the cold shoulder to Bolivia," said Carlos Alberto López, an independent consultant for oil companies in La Paz, "Bolivia will be left with its gas underground."