Publicado por NYTimes.

By PAULO PRADA

Published: May 4, 2006

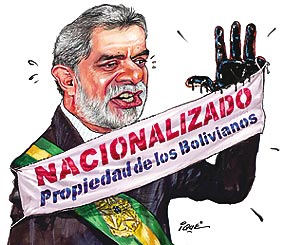

RIO DE JANEIRO, May 3 — President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of Brazil continued his low-key approach on Wednesday to Bolivia's move to take control of its natural gas and oil industries, drawing a barrage of criticism here for what many consider Brazil's weak response.

Brazil is Bolivia's biggest natural gas customer, with more than half its supply coming from there, and Brazil's state-controlled energy company, with over $1 billion invested, is the biggest single investor in Bolivia's natural gas industry. But Mr. da Silva, who publicly applauded the rise of a fellow leftist, Evo Morales, to Bolivia's presidency last December, has offered a muted response since Bolivia announced on Monday that it would take control of its energy industry. Bolivia has South America's second largest natural gas reserves, after Venezuela.

Businesspeople, political opponents and large-scale consumers of natural gas in Brazil, which has South America's biggest economy, say Mr. da Silva was caught flat-footed by Bolivia's move and has been unwilling to parry decisively because of political affinity with Mr. Morales.

"Brazil should have seen this coming," said Rubens Barbosa, a former Brazilian ambassador to the United States now working as a business consultant in São Paulo. "Because of his ideology," Mr. Barbosa said, "the president was ill prepared to defend Brazil's commercial interests."

Aside from securing a guarantee from Mr. Morales that Bolivian gas would keep flowing to Brazil, Mr. da Silva has limited his reaction to saying he would negotiate with Bolivia on Thursday to protect Brazilian interests while respecting the laws of Bolivia. At a speech in Brasília on Wednesday, Mr. da Silva played down talk of a crisis between the countries, even defending the rights of the "suffering people" of Bolivia, South America's poorest nation, to "claim greater power over the greatest riches they have."

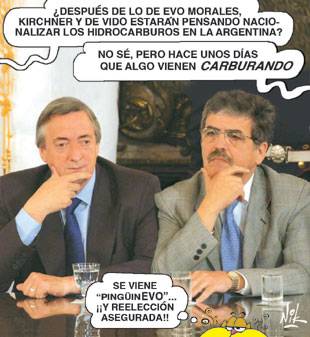

At a meeting on Thursday in Puerto Iguazú, Argentina, Mr. da Silva plans to begin negotiations with Mr. Morales in the company of Presidents Néstor Kirchner of Argentina and Hugo Chávez of Venezuela. Though Mr. Morales is unlikely to reverse the major points of his decision, which requires all foreign operators to sell oil and gas produced in Bolivia through its state-owned energy company, Brazil hopes the presence of the two other leaders, both sympathizers of Mr. Morales, will help Brazil and Bolivia find common ground.

Aldo Rebelo, a former minister in Mr. da Silva's government and now an important ally as president of the lower house of Congress, said mutual interests between the two countries should help them work toward a settlement. Bolivian gas, for instance, fuels much of Brazil's industry and a growing number of power plants fired by natural gas. Revenues from those gas exports give Bolivia roughly one-third of its tax revenues.

"There are too many interests at stake for Brazil not to find an agreement that both protects our commercial interests and enables Bolivia to implement the goals of a democratically elected government," Mr. Rebelo said.

Many critics contrasted Mr. da Silva's reaction to that of Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero of Spain, who warned Bolivia not to harm the interests of the Spanish oil company Repsol-YPF S.A. Repsol, one of the biggest oil companies operating in Latin America, is the second largest investor in Bolivia. The biggest is Petróleo Brasileiro S.A., or Petrobras, the Brazilian energy giant whose southern Bolivian oil fields served as the staging ground for Mr. Morales's decree.

Some political analysts say Mr. da Silva's soft rebuttal to Mr. Morales is calculated. A tougher reaction, they contend, could prompt Bolivia to be more aggressive in increasing its share of the profits as it negotiates new contracts with foreign investors, as stipulated by its decree.

Though Mr. da Silva has yet to declare his candidacy, as expected, for a second term in presidential elections next October, higher energy prices would not sit well with voters.

"There is tremendous concern of a high, short-term increase in gas prices," said Christopher Garman, director of Latin American research at Eurasia Group, a consulting firm. "Brazil wants to work gently toward an acceptable compromise."

By PAULO PRADA

Published: May 4, 2006

RIO DE JANEIRO, May 3 — President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of Brazil continued his low-key approach on Wednesday to Bolivia's move to take control of its natural gas and oil industries, drawing a barrage of criticism here for what many consider Brazil's weak response.

Brazil is Bolivia's biggest natural gas customer, with more than half its supply coming from there, and Brazil's state-controlled energy company, with over $1 billion invested, is the biggest single investor in Bolivia's natural gas industry. But Mr. da Silva, who publicly applauded the rise of a fellow leftist, Evo Morales, to Bolivia's presidency last December, has offered a muted response since Bolivia announced on Monday that it would take control of its energy industry. Bolivia has South America's second largest natural gas reserves, after Venezuela.

Businesspeople, political opponents and large-scale consumers of natural gas in Brazil, which has South America's biggest economy, say Mr. da Silva was caught flat-footed by Bolivia's move and has been unwilling to parry decisively because of political affinity with Mr. Morales.

"Brazil should have seen this coming," said Rubens Barbosa, a former Brazilian ambassador to the United States now working as a business consultant in São Paulo. "Because of his ideology," Mr. Barbosa said, "the president was ill prepared to defend Brazil's commercial interests."

Aside from securing a guarantee from Mr. Morales that Bolivian gas would keep flowing to Brazil, Mr. da Silva has limited his reaction to saying he would negotiate with Bolivia on Thursday to protect Brazilian interests while respecting the laws of Bolivia. At a speech in Brasília on Wednesday, Mr. da Silva played down talk of a crisis between the countries, even defending the rights of the "suffering people" of Bolivia, South America's poorest nation, to "claim greater power over the greatest riches they have."

At a meeting on Thursday in Puerto Iguazú, Argentina, Mr. da Silva plans to begin negotiations with Mr. Morales in the company of Presidents Néstor Kirchner of Argentina and Hugo Chávez of Venezuela. Though Mr. Morales is unlikely to reverse the major points of his decision, which requires all foreign operators to sell oil and gas produced in Bolivia through its state-owned energy company, Brazil hopes the presence of the two other leaders, both sympathizers of Mr. Morales, will help Brazil and Bolivia find common ground.

Aldo Rebelo, a former minister in Mr. da Silva's government and now an important ally as president of the lower house of Congress, said mutual interests between the two countries should help them work toward a settlement. Bolivian gas, for instance, fuels much of Brazil's industry and a growing number of power plants fired by natural gas. Revenues from those gas exports give Bolivia roughly one-third of its tax revenues.

"There are too many interests at stake for Brazil not to find an agreement that both protects our commercial interests and enables Bolivia to implement the goals of a democratically elected government," Mr. Rebelo said.

Many critics contrasted Mr. da Silva's reaction to that of Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero of Spain, who warned Bolivia not to harm the interests of the Spanish oil company Repsol-YPF S.A. Repsol, one of the biggest oil companies operating in Latin America, is the second largest investor in Bolivia. The biggest is Petróleo Brasileiro S.A., or Petrobras, the Brazilian energy giant whose southern Bolivian oil fields served as the staging ground for Mr. Morales's decree.

Some political analysts say Mr. da Silva's soft rebuttal to Mr. Morales is calculated. A tougher reaction, they contend, could prompt Bolivia to be more aggressive in increasing its share of the profits as it negotiates new contracts with foreign investors, as stipulated by its decree.

Though Mr. da Silva has yet to declare his candidacy, as expected, for a second term in presidential elections next October, higher energy prices would not sit well with voters.

"There is tremendous concern of a high, short-term increase in gas prices," said Christopher Garman, director of Latin American research at Eurasia Group, a consulting firm. "Brazil wants to work gently toward an acceptable compromise."