By JUAN FORERO

Published: May 8, 2006

LA PAZ, Bolivia, May 7 — For 24 years, Nelson Cabrera has been there for Bolivia's state-owned energy company — when it was an unwieldy giant of 5,000 workers, when it was sold piece by piece in a divisive privatization, when it got a new boost from the election of Evo Morales, the presidential candidate who promised to restore its old glory. Now, after Mr. Morales nationalized Bolivia's oil and gas reserves last week to the alarm of foreign energy executives, Mr. Cabrera will have a central role in turning what is in essence a bookkeeping company into an energy corporation.

As chief of operations, a promotion he received just three months ago from his job as an engineer, Mr. Cabrera will help guide the company, Yacimientos Petroliferos Fiscales Bolivianos, known as Y.P.F.B., on the mission it once held: exploring, producing and selling Bolivia's greatest resource, natural gas.

"We are going back to exactly what we were before," he said. "We want to think big, we are ambitious, and we are convinced Bolivians have the capacity to take this on."

The challenge, though, will be formidable, perhaps even impossible, for a company that until last year had an operating budget of just $89 million and a staff of 200. Most of the employees are auditors and accountants who studied contracts and other documents filed by the multinationals that took over most Y.P.F.B. functions when the privatization wave hit Bolivia in the mid-1990's.

Many people who opposed the nationalization, including former employees, energy analysts and politicians, are saying that Mr. Morales's audacious move could expose Bolivia to serious economic risk if foreign investment dries up and the company cannot take up the slack.

"It's a bad idea, an idea that's not going to work," said Carlos d'Arlach, a geologist at the company from 1969 to 1979 and who ran it for six months last year. "Over the years, we have seen that to maintain this kind of industry and get ahead you need capital and technology, and we have neither of those."

What many Bolivians do have is a mix of euphoric nationalism and a driving resentment that the prosperity promised through privatization never trickled down to the country's nine million people. Mr. Morales rode that wave of public sentiment, which forced out two presidents in 20 months, to the president's office, largely with promises to nationalize the gas sector.

"Now is the moment to recuperate our sovereignty and dignity," said Jorge Alvarado, the company's president. "We want to show that Bolivians can run our hydrocarbons industry."

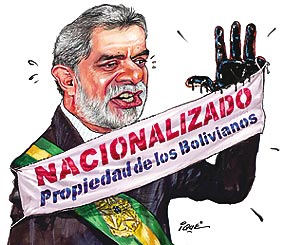

But the decree, announced as soldiers secured the installations of energy companies, incensed energy officials and governments in Brazil, Spain and France, countries whose largest energy companies have plowed more than $4 billion into Bolivia's energy sector. Petrobras, the state-owned energy giant in Brazil and the biggest investor in Bolivia's gas industry, announced that investments here had been suspended, and Repsol YPF S.A. of Spain has hinted that it might try to resolve the issue through international arbitration.

Still, Brazil's president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, has said that he wants to help Bolivia alleviate its poverty and that "being gentle is better than being tough." A Spanish delegation met with Bolivian officials on Friday and announced a willingness to continue negotiating. Those developments have made Bolivian energy officials optimistic that foreign companies are still willing to invest to help Y.P.F.B. become an equal partner in future projects.

"With these companies, we can create joint projects and work together," Mr. Alvarado said. "We put up the primary resource, the gas, which we own, and the investors put up the capital."

The company Mr. Alvarado runs was founded in 1936. Even then, Y.P.F.B. never had it easy: it took 17 years to perforate its first well. It also became a revenue-generating engine for the government, with most of its returns heading into the central government's budget. That ensured that the company never got the development capital it needed. At the same time, corruption plagued it.

In the 1990's, the company was privatized in stages. Foreign companies bought two divisions that produce gas — Chaco and Andina — and one that transports gas, Transredes. The three companies continue to operate under foreign control.

"Y.P.F.B. basically disappeared under capitalization," said Eduardo Gamarra, a Bolivian who leads the Latin America program at Florida International University in Miami. "They have re-refounded it now. But it's a state-owned company that's cash-starved. It needs some access to money quickly."

Perhaps the most encouraging signs come from President Hugo Chávez's leftist government in Venezuela, which has vowed to help Mr. Morales. Rafael Ramírez, Venezuela's energy minister, said Venezuela's state-owned oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela, would invest in Y.P.F.B.'s restructuring, starting with a $40 million plant. Venezuelan technicians are also helping audit foreign companies.

"We have an energy cooperation accord," Mr. Cabrera said. "They've come to do business here, to have a partnership with Y.P.F.B."

The steps being taken, while certainly rife with pitfalls, are exhilarating for Mr. Cabrera and for company officials who felt that the privatizations of the 1990's amounted to "armed robbery," as the energy minister, Andrés Soliz, once put it.

"They fooled us, they swindled us, they took our self-esteem," Mr. Cabrera said.

Mr. d'Arlach and other energy analysts, though, said that, in aiming to become an explorer and producer, the company is not taking into account that Bolivia has discovered plenty of gas and must now line up buyers. Unlike oil, natural gas is much harder to market and is less valuable. And many producers have reserves that dwarf Bolivia's.

"To get involved in exploration would take a long time because it is expensive and risky," he said. "The issue now is not to find more gas because we cannot sell the reserves that we have."

Carlos Arze, an economist and energy specialist, said that the decree underscores the inherent weakness of Y.P.F.B. It calls for the state to have a majority stake in the two gas production companies it once owned, Chaco and Andina, yet they do not produce nearly as much as Petrobras or Repsol. "It will not be dominant in the sector," he said.

Mr. Cabrera is the first to acknowledge that "once you get into the oil business, you need a lot of money." But he said financing could come from loans, sales of gas through company-controlled service stations, and innovative contracts in which Bolivia pays foreign companies for their help with natural gas production.

Venezuela Sets Oil Extraction Tax

CARACAS, Venezuela, May 7 (AP) — President Hugo Chávez said Sunday that Venezuela would impose a new oil extraction tax in a plan to increase revenue from its petroleum industry. "The companies that are pumping oil in Venezuela are making a lot of money," he said in announcing the tax on his weekly television and radio program.